What exactly is Turing Completeness?

An armory for the insatiable pedant

I hear the term Turing Completeness thrown around a lot more in software engineering than I would expect. I think there’s a little confusion about what Turing Complete means, especially within a software engineering context.

We say that Turing Completeness is a property of a computational system that states that the system is as computationally powerful as a Turing machine. But what EXACTLY does that mean? Put your scuba gear and wetsuit on because we’re diving deep into formalism:

Turing Machines

Turing machines are theoretical computers defined by Alan Turing in his highly influential paper titled On Computable Numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem, published 1936. Turing machines are abstract mathematical constructs that help us describe in a rigorous fashion what we mean by computation.

There are countless in-depth tutorials on how a Turing machine works, and you can watch any of them! I can pretty much guarantee that they’re going to be better at explaining how a Turing machine works than me, but in case you don’t want to watch any of those, I’ll throw my description in as well.

A Turing machine consists of 2 elements: The computational head and an infinitely long tape. The head operates roughly as a ‘read-write’ head on a disk drive, and the tape is divided up into an infinitely long set of squares, for which on each square a symbol can be written or erased. The Turing machine recognizes and can write down a finite set of symbols, called the Turing machine’s alphabet.

The Turing machine is only ‘aware’ of one square on the tape at a time — namely the square the head of the Turing machine is currently on.

On that tape, a Turing Machine can do any of these 4 actions:

- Move the head left by 1 space

- Move the head right by 1 space

- Write a symbol at the head

- Erase a symbol at the head

The machine decides which of these operations to do on any given step through a finite state machine. Different Turing machines have different state machines that define their operation.

A finite state machine consists of a finite number of states (which Turing calls m-configurations) which it switches between on every iteration. The machine can only be in one state at a time, but transitions between them based on the current state and the symbol that the machine is currently scanning. The Turing machine takes the current state and the symbol and looks up what to do in a big table.

A Turing Machine also has a set of accept states that tell the Turing machine to stop executing. If the Turing machine enters any of these accept states, the machine is said to halt and suspends execution forever. That’s all there is to Turing Machines!

…well maybe it’s not inherently obvious what exactly that means and how that can be expressive enough to capture all computation. I almost always see Turing Machines described with a state diagram, which I’ll provide a description for in later versions of this article.

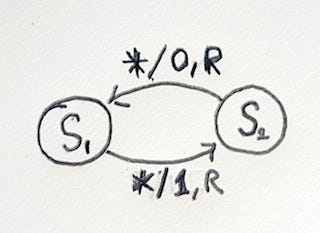

Let’s construct a Turing machine that never halts with a state diagram!

We’ll start out with creating a very simple Turing machine with an alphabet of {0, 1}. We start in state S1, and decide what to do. For any symbol (denoted *) on the tape, the Turing machine writes the symbol 1, moves one space to the right, and switches to S2. Now in state S2, for any symbol on the tape, the machine writes 0 and moves one space to the right, switching to S1. Back in S1, the loop repeats itself, continuing forever. As you might guess, this writes out 1010101[…] in a never ending loop. The machine has no accept states so it will never halt.

Well, that was exciting.

Description Numbers

It turns out we can number all Turing machines uniquely. A Turing machine which doubles a number might be numbered:

31332531173113353111731113322531111731111335317whereas one that triples numbers might be numbered something else:

3133253117311335311173111332253111173111133531731323253117As you can tell, they’re huge and weirdly repetitive numbers, but they are still nonetheless numbers.

We call these the description number for a given Turing machine. We don’t need to specify exactly how to number the Turing machines, it’s sufficient for our purposes to simply note that you can fully encode a Turing machine within an integer.

Spoilers: we’ll pass a Turing machine’s description number as the input to another Turing machine later on, but forget you heard anything…

…as a way of computing functions

Turing machines are fine and all as little toy computers, but what we really want to do is use them to define functions. Turing was a mathematician, and he cared about defining a set of numbers called the computable numbers, and to do so he proposed Turing machines.

In particular, we want to turn Turing machines into partial functions, functions for which there can be undefined outputs. We’ll want these functions to be ℕ⁽ⁿ⁾→ℕ, meaning they take any number n natural numbers as input, and output one natural number (or are undefined for that input, since they are partial).

All we have to do to turn a Turing machine into a partial function is to equip it with an input and output schema. Turing himself doesn’t provide an unambiguous ‘input’ format, but as we get into programming languages, it’ll be useful to make this step of defining input vs. output explicit. I’m choosing a monadic notation as given in Computability and Logic.¹

Precise Formulation

(a) The arguments m1...mk of the function will be represented in monadic notation by blocks of those numbers of strokes, each separated from the next by a single blank, on an otherwise blank tape. Thus at the beginning of the computation of, say, 3 + 2, the tape will look like this: 111B11(b) Initially, the machine will be scanning the leftmost 1 on the tape, and will be in its initial state, state 1. Thus in the computation of 3 + 2, the initial configuration will be 1₁11B11. A configuration as described by (a) and (b) is called a standard initial configuration.(c) If the function that is to be computed assigns a value n to the arguments that are represented initially on the tape, then the machine will eventually halt on a tape containing a block of that number of strokes, and otherwise blank. Thus in the computation of 3+2, the tape will look like this: 11111.(d) In this case, the machine will halt scanning the leftmost 1 on the tape. Thus in the computation of 3 + 2, the final configuration will be 1ₐ1111, where the ath state is one for which there is no instruction what to do if scanning a stroke, so that in this configuration the machine will be halted. A configuration as described by (c) and (d) is called a standard final configuration (or position)(e) If the function that is to be computed assigns no value to the arguments that are represented initially on the tape, then the machine will either never halt, or halt in some nonstandard configuration such as Bₐ11111 or B111ₐ11 or B11111ₐ.

The set of functions that you can express with Turing machines in this manner are called the computable functions.

The exact definition we choose for input and output isn’t that important: As long as translation between different input and output formats is computable (which it almost certainly is for any sane definition), we will get an equivalent set of computable functions.

This is why the oft-heard description “A Turing-complete language is one that can simulate a Turing machine” is absolutely correct, but just a tad misleading. If you can simulate a Turing machine, then you can compute every function that any Turing machine can compute, but the thing that actually makes the system Turing complete is that it can compute the whole set of Turing computable functions.

Computable Numbers

Now, given that we have a solid definition for computable functions, we can sort of ‘bootstrap’ off of that to define the computable numbers. But given that a number can have an infinite number of nonrepeating digits (e.g. something like pi), we have to be just a tad clever in how we define them. Some smart people came up with this:

A computable number a is a number for which there exists some computable function f such that f(n) yields the nth digit of a.

Whoops, Wikipedia tells me that’s not quite right. Let’s swap it out:

A computable number a is a number for which there exists some computable function f such that f(n) satisfies this one weird inequality.

The intuitive sense is the same either way: If you can calculate a number to arbitrary precision, that number is computable.

It turns out a whole host of numbers are computable. Here’s a quick taste:

- All Rational Numbers

- e

- π

- φ

- Any computable function of any computable number

- Almost every number you can think of, really

The point is we can do a heck of a lot of math using only the computable numbers. Computable numbers make up most numbers we think about on a daily basis — enough so that it’s actually kind of hard to think of numbers that aren’t computable.

The Universal Turing Machine

The Universal Turing Machine(UTM) takes another Turing machine’s description number as input, and ‘simulates’ it. That is, the UTM’s output is the same as the Turing machine corresponding to the description number when that Turing machine is given a blank tape. Therefore, the UTM has the capability of ‘simulating’ any other Turing machine.

Turing dedicated a fair number of pages to spelling out the whole state transition table for such a Turing machine, presumably because it’s not inherently obvious that a Turing machine should be able to simulate other Turing machines. The duality of a program as data is likely a lot more comfortable to us today than it was to mathematicians back then. Today, we have few qualms with treating a program as data — especially if we’re used to programming languages with first-class functions.

Incomputability

As the term computable functions implies, there are also incomputable functions: functions we can define for which no Turing machine can possibly exist.

And, despite them being hard to construct, there are a LOT of incomputable functions. In fact, almost all functions are incomputable. There are just that many more possible functions than there ever could be Turing machines, so there must be some that Turing machines miss. In the mathematical language, the set of Turing machines is countable, whereas the set of real numbers is uncountably large.

The canonical incomputable function posited by Martin Davis (with an analogous problem in Turing’s original paper) is the Halting Problem. The problem can be stated very simply:

Halting Problem: Given a computer program and an input for said program, does that program ever finish execution?

It’s easy to imagine examples of programs where it’s possible to figure out whether or not the program finishes: If a state repeats itself exactly, or if the program immediately halts, it’s easy to tell whether or not those programs will halt. But try to come up with an algorithm to decide for ANY program, and you’ll find that the problem becomes impossibly hard, quite literally.

Davis proves that this function is incomputable, that no Turing machine can exist that can compute the correct answer. Because this specific problem yields a yes/no answer, it is considered a decision problem, and since it’s incomputable, the problem is deemed undecidable.

You can get more information about incomputability from this charmingly helpful Buzzfeed community post.

…as originally constructed by Turing

Here’s what I thought when I first read Turing’s paper: “Ooh, this is gonna be totally easy, isn’t it? We just match up the terminology in the modern definition we just learned with Turing’s original terminology! It’ll be a straightforward mapping, right?

I mean, just look at the term circle-free! Circle-free’s easy, it reaches it’s final state in a finite amount of time, like lots of explanations of Turing’s original paper on the internet suggests! Just look at the defi…

If a computing machine never writes down more than a finite number of [the symbols 1 and 0], it will be called circular. Otherwise it is said to be circle-free.

[…]

A sequence is said to be computable if it can be computed by a circle-free machine. A number is computable if it differs by an integer from the number computed by a circle-free machine

Wait, that feels backwards. The machine that prints out an infinite number of 1s and 0s, never halting, computes computable numbers? Isn’t that contrary to how we outlined it before, wherein the only defined output was when the Turing machine halted in a standard configuration?”

Unfortunately for my past self, the mapping from the modern definitions to Turing’s original paper isn’t quite so clean, and so requires a fair amount of modification. Let’s throw away all the definitions for computable functions and computable numbers that we spent so much time learning, so that we’re left with the just the Turing machine itself.

Computable Sequences

In fact, Turing’s primary focus was on this idea of computable sequences, which we will use to define computable numbers shortly.

We can look at that non-halting Turing machine we constructed earlier: On a blank tape, it prints 10101010101…. Because this was made by a Turing machine that ends up printing out an infinite number of 1s and 0s, Turing would consider this a computable sequence.

Under Turing’s original construction, these sorts of infinite sequences are exactly what we’re going for — we want to print out a bunch of 1s and 0s forever and ever. We’d call Turing machines that end up printing an infinite sequence like this circle-free, and anything else circular.

From computable sequences to computable numbers

Just like we have decimals in base 10, we can have ‘decimals’ in base 2 as well! They’re not called ‘decimals’, rather ‘binary fractions’, but they operate pretty much exactly the same, except in base 2 rather than base 10. For example, the number 0.75 converted to binary becomes 0.11, or 2.8125 converted to binary becomes 10.1101. The exact conversion between decimal fractions and binary fractions isn’t really important, but you can watch a tutorial if you really want.

We can interpret a computable sequence as the fractional part of a binary number. The sequence 101010… would therefore becomes 0.101010…, giving us a number to work with. Anything that’s off by an integer from this fractional component is itself computable.

It turns out, the set of computable numbers defined by the modern construction and by Turing’s construction are the same!

But… why the modern construction then?

I have no clue what drove the modern construction. I believe it’s clearer and easier to work with mathematically than its original counterpart, but that’s about it. Perhaps there’s some incurable ambiguity in the original construction that makes it not mathematically rigorous enough. If anyone has input on this, I’d love to hear it.

A quick pet peeve

If we’re gonna invoke the language of the original paper when we’re forming arguments (which we shouldn’t have to do anyways), we might at least do so genuinely and accurately. It’s cool to say a Turing machine is circle-free if you actually mean this Turing machine prints out a binary fraction ad infinitum, but try to refrain from doing so when that’s not exactly what you mean.

If you get nothing else out of this article, get this: Being pedantic about Turing machines’ definitions doesn’t get you very far. It doesn’t generally make you more correct mathematically. Most sane definitions of Turing’s initial definition will be equivalent. Unless we’re solving problems within the specific domain of computability, we shouldn’t be arguing about this stuff in any meaningful capacity — it’s not worth it.

Equivalence to other computational systems

So, as I mentioned earlier, there are a fair number of equivalent models of Turing machines. Google these away to your heart’s content.

- Post-Turing Machines

- Multi-tape Turing Machines

And also equivalent models that aren’t Turing Machines:

- μ-recursive functions

- the Untyped Lambda Calculus

- OISCs, highly minimalistic computers with just one instruction.

- Conway’s Game of Life

- Most programming languages

- Abacuses (with a few simple rules)

- Buckets and rocks (with a few simple rules)

- Whichever system Randall Munroe was implying with this

We can prove that in each of these cases, these computational systems can compute the exact same set of functions as any other. And boy, that’s a lot of different Turing equivalent systems. Abaci, recursive functions, the lambda calculus, a bunch of rocks? They’re all exactly equivalent? Huh, weird…

Anyways, let’s take a closer look at programming languages.

Programming Languages as Turing Complete

Intuitively, programming languages can be Turing complete. Let’s see if we can formalize the notion.

Pragmatically, all we have to do to get our programming language into the throes of beautiful formalism is to equip it with an input and output format, just like we did for Turing machines above. Like before, we have some play with exactly how we define our input and outputs, but most reasonable choices should give us all the power we need. We’re not trying to make waves with this choice, we’re just trying to bootstrap to the point where “input” and “output” make sense mathematically.

For a quick example of how dead simple I’m thinking, we’ll do a quick one for javascript:

If a javascript program exposes a function named run() which, when executed with a primitive integer as the first argument, returns either an integer or undefined, the output is the return value. Otherwise the output is undefined.I’m gonna return to this particular definition later, but for right now, just note that it is one of many possible definitions we could choose.

Boundedness

Turing machines can hold an unbounded amount of state, whereas computers cannot.

Any program running on a computer isn’t going to be fully Turing complete; there exists a limit. No computer ever is going to be able to compute Graham’s Number * 2, ever — there’s just not enough space in the universe for a computer that large. Yet, to a Turing machine which doubles numbers, the practical boundedness of the universe isn’t an issue. A Turing machine is just as capable of computing Graham’s Number * 2 as it is computing the 2 * 2, it just takes a few more steps. This gap implies that real world computers can’t compute Turing Computable functions for all inputs, and are therefore not Turing Complete.

So what are they?

We have a separate name for these — they’re not quite equivalent to full-blown Turing machines but they can do everything that a Turing machine can, up to a certain limit. These are called Linear Bounded Automations. Linear Bounded Automations are nearly identical to Turing machines, except they impose a left and right boundary to the tape.

So if computers aren’t fully Turing complete, how can a programming language, which runs on a computer, ever hope to be Turing complete?

The trick is that languages don’t necessarily imply limits within their specifications and instead push this problem to the lower level. A language can either be Turing complete or Turing incomplete, based solely on its specification, and independently of any implementation on a real-world computer. The difference might be more subtle than you think, which I can demonstrate using Brainfuck.²

Let’s compare 2 different common interpretations of the Brainfuck byte pointer:

Original Definition

A Brainfuck program has an implicit byte pointer, called “the pointer”, which is free to move around within an array of 30000 bytes, initially all set to zero. The pointer itself is initialized to point to the beginning of this array.Modified Definition

A Brainfuck program has an implicit byte pointer, called “the pointer”, which is free to move around within an infinite array, initially all set to zero. The pointer itself is initialized to point to the beginning of this array.

Spot the difference? It’s that bound on the tape length. In the former case, the language itself has a finite bound, making it equivalent to a linearly bound automata, independent of any machine it runs on. On a theoretical computer without bounds, the functions expressible by the original definition is NOT Turing complete.

Compare with the bottom definition.³ On a theoretical computer without bounds, we can express any Turing computable function using Brainfuck. Thus the language itself, separate from any implementation or computer it might run on, is Turing complete.

So when someone says “language [x] is Turing complete” and doesn’t prove that the language itself can theoretically support unbounded memory, you can out-pedant them and tell them that you won’t believe them until they show it does!

…speaking of which, let’s go back to the definition for input and output we chose for Javascript. We’ll do a sanity check to see whether or not our input and output allow for ANY size number, up to and beyond Graham’s Number. Here’s what we laid out before:

If a javascript program exposes a function named run() which, when executed with a primitive integer as the first argument, returns either an integer or undefined, the output is the return value. Otherwise the output is undefined.So does that work with mind-bogglingly huge numbers like Graham’s number? Unfortunately, no. In Javascript, primitive integers are only guaranteed exact to 2⁵³, so it looks like this specific input/output schema wasn’t sufficient.

Establishing an Input/Output schema for Javascript

So what input/output schema would be viable? Can we use strings to represent infinite data? Not anymore. Can we use very large unary arrays to represent numbers? Sadly, no.

Let’s move to a different data structure, away from primitives for input, and consider using instead a linked list of various objects in JS. Remember, we’re just looking for a viable way to represent natural numbers:

// null wrapped 3 times represents the number 3

{ next: { next: { next: null }}}This schema should work⁴. The only limit to how deeply this structure can nest are limits in the interpreter and computer themselves — not within the spec. We can, as far as the Javascript specification is concerned, represent numbers as large as Graham’s number using this recursive pattern.⁶

Does this mean Javascript is Turing complete? We should avoid jumping to conclusions too early: There might be some critical roadblock to handling extremely large recursive structures, but for JavaScript, I doubt there’s any such roadblock.⁵

Hypercomputation in Programming Languages

The ability to specify non-implementable processes has an interesting implication: A programming language’s specification need not be bounded by computability. That is, a programming language itself can be specified to be Super-Turing complete, able to compute things a Turing machine never could.

For example, imagine something called JS-Hyper. JS-Hyper is equivalent to JS, with the addition of a new builtin function willHalt(dn, args), where willHalt is an oracle that determines whether the Turing machine with description number dn will halt for arguments args. Since a Turing machine can’t compute that function, JS-Hyper is Super-Turing complete

This serves to show that even though we expect computers to be able to execute programming languages, nothing stops us from defining a programming language unconstrained by such silly notions such as computability. We can do anything we want! The power is ours! Haha!

The Church-Turing Thesis

Why should we care so much about this weird set of functions called the computable functions? Why does it even make sense to call this set of functions the computable functions?

What Turing and Alonzo Church claim is that humans are bound by these rules just like machines are; that any process a human can use to calculate a number can also be done by a computer, and vice versa. The Church-Turing thesis, in essence, claims that human beings are (computationally at least) Turing Equivalent.

Turing calls the numbers that humans can algorithmically compute in finite time the effectively calculable numbers. In essence, the effectively calculable numbers are all the numbers we’d ever have hope of computing — any number wherein we can think of a method to compute that number is considered to be effectively calculable.

We can restate the Church-Turing thesis in this language, yielding:

Church-Turing Thesis: The sets of effectively calculable numbers and computable numbers are equivalent.

Looks almost formal, doesn’t it?

And away from rigor

As you might have noticed, the Church-Turing thesis isn’t an argument based on strict formalisms or on rigorous proofs. No, we’ve strayed deep into what is essentially a philosophical argument about the limits of computability and of minds themselves — a wonderful example of philosophy and mathematics coexisting and complementing one other.

Turing’s argument provides three pieces of evidence to make his case for the equivalence of the effectively calculable numbers and the computable numbers.

The arguments which I shall use are of three kinds.

(a) A direct appeal to intuition.

(b) A proof of the equivalence of two definitions (in case the new definition has a greater intuitive appeal).

(c) Giving examples of large classes of numbers which are computable.

We’ve already brought up equivalent systems before, and we’ve also brought up large classes of computable numbers as well (neither of which we’re bothering to prove here). So that just leaves the direct appeal to intuition to complete Turing’s argument.

In essence, Turing argues that the process a computer (as in the old school human occupation) executes to compute a number essentially boils down to an infinite tape paired with a finite state machine. A human can focus on only at a finite number of symbols at a time, and a human only has a finite number of possible head-states (due to a finite number of neurons). Given that a certain head-state defines what action you take next, you can imagine a massive, massive transition table, encompassing every possible mental transition.

Obviously, this is a very rough sketch argument. But at least you can sort of see how a combination of infinite paper and finite mental capacity hints towards the Church-Turing thesis.

Broader implications

What’s so interesting about the Church-Turing thesis philosophically is that it points towards Turing completeness as being ‘it’, in a sense. It points towards no deterministic system being able to compute more than what a Turing machine can compute. In this sense, incomputable means not only incomputable for Turing machines, but for ANY type of deterministic machine.

Given how many systems are Turing equivalent, how simple a system can be to be Turing equivalent, and how prevalent Turing equivalence is, does it still make sense to think of Turing completeness in terms of Turing machines? Maybe pragmatically, but in my opinion, these machines shouldn’t form the essence of Turing computability, rather merely the origin of Turing computability.

To me, thinking about Turing equivalence as being inexorably bound to Turing machines kind of devalues how fundamental computable numbers and computable functions are. This set of functions has deep mathematical and philosophical importance separate from how we defined them; Turing machines just happened to be how we bootstrapped ourselves to understanding what they are. I think that’s really cool.

Tackling the incomputable

Can we go beyond these restrictions? What tools do we have against the uncountably many incomputable numbers? You might be tempted to think that there’s no way for a computer to compute anything uncomputable — I mean, it’s exactly what Turing claims!

Well, our edge against these problems lies in not solving the general problems that are proven incomputable, but tackling specific sub-problems that it might be useful to solve anyways. If we had a program that verified whether a certain program would terminate or not for most programs (but not all), that’s something we can use to help us write algorithms and proofs. Pathological cases need not stop us from providing answers in straightforward cases.

In software engineering, we solve specific subproblems like this all the time. So often, in fact, we might not realize what we’re doing. For example, does this JS program ever finish execution?

function run(){

for(let i = 0; i !== -1; i++);

}The answer is “No, of course not. i will never equal -1, so this program will run forever.” Well, you just performed a little subproblem of the great and undecidable halting problem, and it wasn’t even difficult! Yay!

Compilers automate this process heavily, deciding whether code is unreachable, whether certain subroutines will ever stop, so on and so forth. In essence, compilers solve the halting problem in specific cases, just like we did above. If we extend this kind of reasoning, we can cover some pretty complicated examples.⁷

Hypercomputation

There is, however, a field of study called hypercomputation that deals with the calculation of incomputable numbers. Like actual, real, manifestable incomputable numbers in the real world. Hypercomputation as a subject requires either:

- That the Church-Turing thesis is false, such that there exists some mechanical process that humans can do to compute numbers that can’t be performed by computers.

- That the Church-Turing thesis is fundamentally weaker than the common interpretation, such that there exist functions that machines can compute which humans cannot (given infinite time and space).

- That there are physically realizable incomputable numbers, such that there are instances wherein we can measure incomputable numbers physically rather than compute them.

Philosophically, if any of these things are true, then that says something very profound about the nature of the universe: that the universe explicitly does NOT operate like a Turing machine. This might be really interesting to know.

For potentially unsurprising reasons, studying something that relies on one of those three unproven assumptions has led to a number of skeptics. Notably, Martin Davis (the fellow who as mentioned earlier popularized the modern definition of Turing machines), wrote a paper with the wonderfully sassy title The Myth of Hypercomputation. Davis argues that 1: many ‘results’ in hypercomputation either implicitly or explicitly presume having access to incomputable numbers to begin with, and that 2: if there was a manifestation of an incomputable number physically, it wouldn’t be useful.

This controversy ended up prompting one of the better lines in academia, written by Davis in Vol. 178 of Applied Mathematics and Computation:

The editors have kindly invited me to write an introduction to this special issue devoted to ‘‘hypercomputation’’ despite their perfect awareness of my belief that there is no such subject.

I had no other reason to include this mention of hypercomputation except that I find the above quote hilarious and wanted a reason to share it.

Does this field exist? Tell us what you think in the comment section below. Don’t forget to rate, comment, and subscribe for more videos like this!

Is Turing computability useful knowledge in software engineering?

There’s a lot of talk about languages being Turing-complete. I don’t think this is a very useful consideration, for several reasons:

- It’s not a high bar. You wouldn’t differentiate a programming language as being Turing complete, given that practically every other programming language for which Turing completeness matters is itself Turing complete.

- Whether a language is fully Turing complete vs. linearly bounded isn’t a very useful distinction, because we run our programs on computers of finite size and speed, not within the boundless logic-sphere of mathematics, and most language-specified bounds are going to be large enough for any purpose.

- Turing completeness doesn’t make a language useful. I mentioned earlier that Brainfuck is Turing complete, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to consider it for any serious project. Languages in this category are said to fall into the Turing Tarpit.

- Turing incompleteness doesn’t make a language useless, either. If HTML ends up being Turing incomplete, that doesn’t make HTML any less useful: It’s a tool to specify document structure. It doesn’t need to be Turing complete.

So if it ever is useful in arguments about software engineering, it’s rarely useful at best. Any argument in software engineering hinging on Turing completeness either misunderstands Turing completeness or forms a particularly weak claim.

Fortunately, people don’t care purely about the immediate utility of information. That would be fairly annoying.

Is this article over?

Yes.

Sources include Computability and Logic, The Annotated Turing, lots of Wikipedia, all papers mentioned (and a few others now long gone in my browser history), assorted blog posts, conversations about computability with friends, a few of my own arguments, and hopefully comments from Viewers Like You. Thank you.

If I’m wrong about ANYTHING, regardless how pedantic, feel free to comment and tell me about why. I have no formal background in theory of computation, so it’s very likely I got something wrong here, just hoping it wasn’t anything too major.

Footnotes

(1): The definition I chose to use here differs only minimally from Kleene and Martin’s description of the partial function, which requires an extra tally for each input, such that an input of 3 would be encoded 1111, rather than 111. I’m not sure why Computability and Logic chose to stray from that, but this isn’t a wildly important difference.

(2): If you haven’t encountered Brainfuck before and you’re a big enough nerd to have made it this far into an article about Turing completeness, you’re in for a treat: It’s a hilariously minimalistic and hard to use programming language. Seriously, try it out!)

(3) I believe this is the definition implicitly used in Brainfuck is Turing Complete

(4) It might have been more convenient to use nested arrays, such as [] to represent 0, [[]] to represent 1, so on and so forth. I thought objects would capture the nature a bit better.

(5) In this case, we can paint some strong intuition why we likely don’t have such an issue. Remember the untyped lambda calculus I mentioned earlier? It uses a recursive structure to represent unary numbers in a very similar fashion, and one could easily define a translation between the above linked list representation and the Church Numerals that the untyped lambda calculus uses. Since the operations on the lambda calculus are defined recursively, and (I don’t think) there is any spec-defined limit on recursion depth, this format should be sufficient. Javascript is almost certainly Turing complete.

(6) To me, it seems like our looser sense of “Is this system Turing Complete” implicitly asks “Does there exist an input/output strategy such that the resulting system is Turing Complete?” I’m not going to dig into this problem, because doing so opens up the can of worms in terms of “well what defines an input/output schema? Could that alone be Turing-complete?” and I’m not yet equipped to tackle those questions. We’ll just have to plug our ears and close our eyes and pretend we haven’t thought of this minor complication.

(7) I believe this is what Microsoft’s Terminator research project was trying to tackle, but I don’t know what’s up with that or where the current state of the art is.